Image

March is women’s history month. There are many women throughout history who never got the recognition they deserved,. Today, however, we have the resources to research and rectify past injustices toward women. Here’s a list of five remarkable women, and what they did to change the world.

Hedy Lamarr

Publicity Photo of Hedy Lamarr, c. 1944

Publicity Photo of Hedy Lamarr, c. 1944Hedy Lamarr was born in Vienna, Austria in 1914 to a Jewish family. Her given name was Hedwig Kiesler.

From a young age, Lamarr was exposed to STEM and the arts. Her father would bring her to museums and discuss with her how machinery worked, while her mother would enroll her in dance and piano lessons. By the age of 5, she could take apart her music box and put it back together, understanding how each part worked to produce the sound.

At 16 years old, Lamarr was discovered for her beauty by the director Max Reinhardt. She studied acting with him and was cast in a small film. She soon grew more popular as she was cast in the film Ecstacy in 1933 which was controversial, as Lamarr was in the nude in a few scenes.

The same year, Lamarr got married to a man called Fritz Mandl. He didn’t want her working. He had Nazi friends who he would invite to dinner parties. She was forced to host these people who did not see her as the human being she was. These people would openly talk about war weapons in front of her, likely assuming that she wouldn’t do anything with this information.

Four years into the marriage, Lamarr escaped from Mandl by fleeing to London. There, she was offered an opportunity to go to Hollywood, and she took it. The one condition of this trip was that she get rid of her “scandalous” name and assume a different one. This was when she started using the surname Lamarr.

In California, she met a man named Howard Hughes. He was a businessman and a pilot. He encouraged her scientific mind and gifted her with a small set of equipment she could use in her trailer in between takes of her movies. She also had an inventing table in her house.

Hughes took Lamarr to meet with scientists and look at plane designs. She was inspired by this and researched what the fastest birds and fish were, and incorporated their wing and fin designs into a new plane design that could be used for war.

Lamarr also invented an updated stoplight and a tablet that turned into a cola-type beverage when put in water.

With the threat of a World War looming, Lamarr didn’t feel comfortable sitting in Hollywood when she could be using her knowledge to fight.

She and a man named George Antheil came up with a new communications system that was intended to guide torpedoes to where they were aimed. They used “frequency-hopping” technology among radio waves, and since there were no interfering waves, the torpedo hit its target. They sold the patent, but the Navy rejected its use.

Lamarr continued to make films until 1958 but never received recognition for her innovations until 1997 when she and Antheil were awarded the Pioneer Award by the Electronic Frontier Foundation for their frequency-hopping technology. This advancement paved the way for Wifi and Bluetooth, dubbing her the “Mother of Wifi.”

In 2000, Lamarr passed away after withdrawing to her home for the years before. In 2014, she was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame for her frequency-hopping technology.

Gladys Bently

Gladys Bentley by an unidentified photographer, c. 1940

Gladys Bentley by an unidentified photographer, c. 1940Gladys Bently was born in Philadelphia in 1907. Growing up, she wore her brothers’ suits and clothing, but her parents disproved of this and brought her to doctors to “cure” her.

At 16 years old, Bently ran away to New York City where she began to sing at rent parties and buffet flats. She then moved to speakeasies and nightclubs where she got more popular. Throughout this time, she did not hide her sexuality or gender expression. She regularly sang songs about other women and dressed in tuxedos.

Between 1928 and 1929, in her early 20’s, Okeh Race Records released eight singles of Bentley’s. She had her own weekly radio program the next year.

In 1933, Bentley headlined in nightclubs and theaters like the Apollo. Her performances could end with the police shutting them down because of foul language and her sexuality. She had backup singers who would also dress masculinity while singing effeminately.

While some people had a problem with Bentley’s appearance and the content of her music, many did not. She was a star in New York City nightclubs, even as she openly flirted with women in her audiences.

Bentley lived with her lover, who was both white and a woman. This was seen as scandalous on many different levels. They had a civil union recognized in New Jersey, which was the closest to getting married they could get in the 1930s.

As Prohibition ended, however, so did her popularity in the city. Many white people were no longer looking for entertainment in Harlem, where Bentley performed. She moved to Los Angeles with her mother and eventually gained more success during World War II. She performed at clubs and bars but in a “toned down” version of what she did in New York.

In LA, she started wearing dresses again. By the 1950s, the country was more conservative than in Bentley’s earlier years. Someone who identified as gay would have been considered more of a threat than before. Bentley had to assume the role of a more traditional Black woman.

Bentley went even as far as to suggest that she had been “cured,’ which many historians believe had to do with McCarthyism, and claims that homosexuality, along with communism, was a great threat to the United States. Bentley had to protect herself, even if it meant giving up parts of herself.

In 1960, Bentley caught pneumonia and passed away at the age of 53.

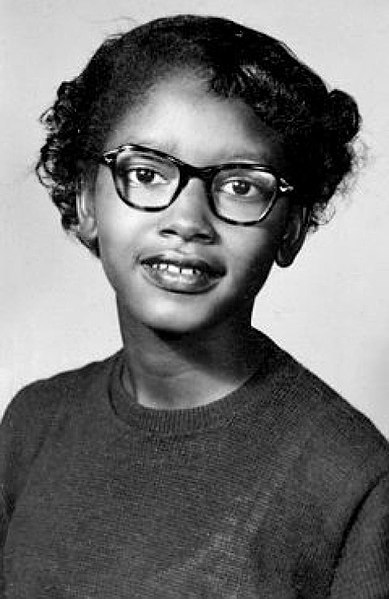

Claudette Colvin

Claudette Colvin c. 1953

Claudette Colvin c. 1953Claudette Colvin was born September 5, 1939, in Birmingham, Alabama. She was born Claudette Austin, but soon, she and her sister were taken in by their aunt and uncle, and given their last name, Colvin.

Colvin was exposed to prejudice since childhood in Montgomery, Alabama. She had a friend who was put to his death for flirting with a white girl. She has recalled not being able to try on clothes and shoes in stores, where white people would be allowed to. This injustice against her community, and her academic focus, had Colvin set on becoming a lawyer and fighting for civil rights from a young age. She was a member of the NAACP Youth Council and became close with a mentor, Rosa Parks.

On March 2, 1955, 15-year-old Colvin was on a public bus in Montgomery. The bus soon got crowded and a white woman was left standing while Colvin, and a group of three other Black women were seated. The bus driver demanded that Colvin and the three women move so the white women could sit. The three women moved, but Colvin did not. In fact, another black woman sat down next to her.

The bus driver called for the police.

Colvin was forced off the bus by two police officers while yelling that it was her constitutional right to sit. These men made her fear that she would be raped, based on their violent behavior and lewd comments they made about her body on their way to the station. One of the men sat in the backseat of the car with her.

Claudette Colvin was charged with violating segregation laws, misconduct, and resisting arrest. She was also arrested for assaulting an officer, but that was dropped because a school peer of hers, who was also on the bus, said there was no assault.

The arrest made Colvin fear for her ability to pursue higher education and her dreams of fighting for civil rights in court.

Martin Luther King Jr. went to Montgomery to fight against Colvin’s arrest, as did many others. A lot of African Americans believed that Claudette Colvin could be the face of the Civil Rights movement.

She was not, however, the face of the movement. Nine months after Colvin resisted arrest, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus. She was chosen as the focal point because she was older, more educated, light-skinned, and by that time, Colvin was pregnant.

In 1956, Colvin and the three other women asked to give up their seats brought their case up to the United States District Court for the Middle District of Alabama in the case Browder v. Gayle. The Court decided that bus segregation violated the 14th Amendment.

After this, Colvin was deemed a troublemaker in Alabama and had to withdraw from college. She moved to New York City with her son and worked as a nurse’s aide for 35 years until she retired.

Colvin was not angry about not getting the recognition she deserved, but rather, disappointed. She could have been the face of the Civil Rights Movement, but instead, people listened to the woman who more conformed to the biases that were trying to be eradicated.

Colvin is still alive today at age 83.

Isabella Goodwin

Isabella Goodwin c. 1915

Isabella Goodwin c. 1915Isabella Goodwin was born on February 20, 1865, in Manhattan. She got married at 19 years old to a policeman and had 4 children with him before he died in 1896.

As they did with many widows of officers, the NYPD offered Goodwin a job to support her family. She started out by mostly cleaning cells and supervising inmates, but in 1912, Goodwin went undercover.

There had been a bank heist in broad daylight that made national news. A man named Eddie Kinsman, and accomplices of his hijacked a taxi, injured and robbed the driver and his guard, and drove to a getaway car that had no license plates.

The police had no leads and had started to lose hope when they heard a rumor about Kinsman, and two people who might know his whereabouts: Swede Annie Hull and Myrtle Hoyt.

Swede Annie Hull was the girlfriend of Eddie Kinsman, and her roommate was Hoyt. Goodwin went undercover as a maid for the women.

Goodwin spent her time cleaning, running errands, cooking, and sleuthing. She lived in a dark room under the stairs, ate scraps of the women’s meals, and thrived on strong coffee. She eavesdropped through walls and keyholes and reported her findings back to other detectives early in the mornings before she could be noticed as missing.

One day, Goodwin found an angry Myrtle Hoyt and asked her what was wrong. Through this conversation, Goodwin learned that Kinsman and Swede Annie, after going on a luxury shopping spree, were going to be moving to California. This was quite a shock to Hoyt because they had never had the money before for that lifestyle. This was the first bit of solid evidence Goodwin had against Kinsman.

The police were finally able to arrest Kinsman thanks to this intel. They found him at a train station trying to buy tickets West, just like Hoyt had said.

Goodwin was promoted to detective lieutenant after this case, making her the first female detective in the NYPD. In the next few years, a couple more female detectives were hired, although they were underpaid compared to their male counterparts.

In 1921, Goodwin was picked to lead the department’s new Women’s Bureau, and 3 years later she helped investigate fraudulent medical practices, before retiring later that year.

Goodwin died of colon cancer in October 1943 at the age of 78. Her gravestone reads “Isabella Seaholm” reflecting her second husband’s name.

Her legacy lives on though. In 2011, a book titled The Fearless Mrs. Goodwin by Elizabeth Mitchell was written about her, and in 2014 a series was made called “The Alienist” based on Caleb Carr’s novel of the same name. Dakota Fanning plays Sara Howard, who was based on Goodwin.

Today there are about 6,570 women in the NYPD’s 36,500-member force. They make up about 18% of the department. This includes 781 detectives, 753 sergeants, and 200 lieutenants.

Jane Cooke Wright

Jane Cooke Wright Copyright © 2013 ASCO

Jane Cooke Wright Copyright © 2013 ASCOJane Cooke Wright was born in 1919, in Manhattan. Her father, Louis T. Wright was a doctor, and she followed in his footsteps.

Wright went to medical school at New York Medical College, then residencies at a few different hospitals until she got to Harlem Hospital. She was the chief resident there in 1949.

At Harlem Hospital, Wright worked with her father to help treat cancer. At the time, chemotherapy was not used unless as a last resort and most other drugs were experimental. Jane Cooke Wright and Louis T. Wright performed trials on human cancers and leukemias for newer medicines that had mostly been tested on lab mice in the past.

In this research, they found that methotrexate, one of the chemicals they were testing, was very effective in treating breast cancer and skin cancer. It slowed the growth of the cancer cells. Many patients on this medication and others they tested had remission of their cancers.

To ensure that her work would have an impact on the medical community, Wright, along with a group of 6 doctors who had also experimented with cancer-fighting chemicals, founded the American Society of Clinical Oncology, or ASCO. She was the only woman and the only African American among the founders. The goal of the ASCO was to make oncology research more available and widespread to the public.

In 1955, Wright began teaching surgical research at New York University. She was also made director of cancer chemotherapy research at the school’s medical center.

President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed Wright to the President’s Commission on Heart Disease, Cancer, and Stroke in 1964. She was the first woman appointed to this position. By 1967, Wright was the highest-ranked African American woman at a nationally recognized medical institution.

Wright won many awards and held other high rankings, including the merit Award from Mademoiselle magazine, the Spirit of Achievement Award of the Women’s Division of Albert Einstein College of Medicine, and the Hadassah Myrtle Wreath Award. These were all won within 15 years of each other. In 1971, Jane C. Wright became the woman to serve as the president of the New York Cancer Society.

In 1987, after a 44-year-long career, Dr. Wright retired. She died in 2013 at the age of 93 after impacting the lives of thousands of people.